Report 2: Sui generis database right, functional vs. technical view, caveats of the Japanese TDM exception, [vertical] integration

This is the second of three blog posts about the iCLIC Data Mining and Data Sharing workshop's part on copyright and database law. Some notes are added in "[]". For the overall introduction see the first blog post. The third blog post covers Margaret Haig's and other contributions, panel discussions and Q&As.

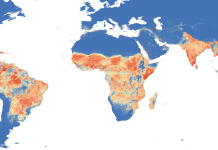

The panel started by outlining the potential of text and data mining (TDM). It is economic value, opportunities for academia and innovation in different sectors, and the potential of enabling people to harness value of information. Ultimately the opportunity is benefits for all. TDM technologies and data science enable us to use information in new ways, to make sense of the complexities of the sea of information, to create answers not possible without those technologies and to use information currently not used at all. It also helps with debugging complex systems, to make them more secure and to better understand and predict them. Sectors benefiting most are probably health care, medical research and the pharmaceutical industries. For scientific, technical and medical (STM) publishers TDM is the future of how scientific information is used and it is within its normal use.

From the audience the aspect of ethical issues was brought in, pointing to a recent paper by Microsoft Research and others on discrimination in text mining. A European Parliament (EP) working group mainly looking into liability issues in robotics addresses ethical questions of Artificial Intelligence (AI). Such ethical issues become increasingly important - in predictive policing, for example. Also in this context it needs to be considered that TDM is a cultural technique, which needs to be learned - and in order to learn it people need to be able to do it in a sound legal environment. We shouldn't mystify TDM as something, which is done only by large companies. It is something everyone can do and often there is no economic rationale behind it.

Dr Eleonora Rosati, who chaired this panel, then switched to the legal part, handing over to Professor Estelle Derclaye, who joined via VoIP. Legal issues mainly of relevance for TDM in the EU context are copyright (2001 InfoSoc Directive) and sui generis database right (SGDR) (1996 Database Directive). Because the definition in the Database Directive of what constitutes a database is very broad, most databases are subject to this right, including many of the corpora being mined and even databases without being corpora already before the TDM activity. Extraction of a quantitatively or qualitatively substantial part of a database or 'scanning' it (and by definition this is what is done with TDM), which both implies reproduction, would be an infringement of this right.

As it is the case in copyright law, there are exceptions for the SGDR, but they are very limited and generally don't apply to TDM uses. Article 9(b) concerns the exemption of uses with scholarly purpose, but with this exception there are many problems: it is limited to non-commercial purposes; it is optional for member states to implement; and the parts that can be used under the exception can only be used for reproduction, i.e. based on the exception you cannot communicate to the public or publish them. Additionally, in most cases the exceptions can be overturned by contract. You would think, if there is an exception, then it ought to apply, but in effect a database basically cannot be data-mined under the exceptions as it is protected in the EU, because it is very difficult to meet those conditions. [Issues concerning contracts/licenses for TDM uses are mentioned in parts 1 and 3 of this blog post series.]

That's where the new Directive proposed by the European Commission (EC) comes in. Estelle noted at the time that she hadn't read in detail the proposal and its recitals yet, but that the TDM exception appears too narrow. It would be better to have a fair use approach or to revisit the reproduction, extraction and communication to the public rights - to the effect that exclusive rights don't include TDM uses as broadly. One reason is that with TDM you are not using the database as a database. It is doing something different. You are not using the database to be in competition with the database provider.

The definition of the reproduction right is not only very broad, but it is also a technical definition, which is not linked to the function of copyright or database right. Some legal scholars suggest that TDM should not be within the scope of this right at all, because with TDM the work is not used as a work, but it is used to do something completely different - TDM would be outside of the function of copyright and database right in the first place and thereby out of the scope where exceptions would be needed. This line of thinking is based on theories being developed in the European context [(.ZIP file download)*; see Prof. Strowel's slides, for example].

The European Court of Justice has a broad view on what constitutes a database and this makes the law even more stringent. In the case Verlag [publisher] Esterbauer v. Freistaat Bayern, concerning extraction of geographical data from maps, the Court has interpreted the definition even broader than before. The extracted elements in question in this case were deemed to still make sense on its own, not only to the typical user of the database, but to anyone. This independence [/ autonomous informative value] of the materials/elements in a collection is one of the definition criteria for what counts as a database under the Database Directive. So, if you extract those elements and do something completely different with it, it would still be an infringement, as it would fall within the scope of the database right.

The question was posed what - if there was a broad exception for TDM - Google would do, if another party would reuse the entirety of Google Maps to prepare another map through TDM. One answer was that Google Maps is based on a tangled web of different licenses from different map copyright owners so that there would be others involved. Trevor Callaghan, not speaking on behalf of Google, pointed out that Google often intersects with rightsholders as an intermediary, but at the same time is one of the biggest rightsholders in the world. Google, in general, might be positive about an exception, because it recognises the value that this drives to technology and usage which is not anticipated.

Carlo Scollo Lavizzari added that, because STM publishers see TDM as the main way in which content will be used, they will publish it adapted to TDM. The Japanese TDM exception has the caveat that if you make a database adapted to TDM, it is not covered by the exception. As TDM becomes an every day way of using information and databases and other tools STM publishers develop and adapt to TDM, he wonders whether those would then [after introduction of a TDM exception] still be protected. "Adapted to TDM" means to make it so that it is suitable for data mining or it is enhanced so that it can interlock with the tools that people have, i.e. making the content usable for the tools. In the pharmaceutical industry the main block for TDM is the trust of researchers in the tool - so, these things must become more integrated.

A few comments followed. If there is substantial investment, then such specialised databases might deserve database right. At the same time, the value question is orthogonal to the Intellectual Property (IP) question - you can have one without the other. If this specialised service/database provided by publishers is so much more useable than people just downloading the articles and doing the TDM themselves, then they probably would be happy to pay for it - but publishers don't need copyright to do this. There is a huge opportunity for publishers to develop TDM tools and charge for the use of those tools (and not for the [TDM-]use of the content). You can have articles so that they are accessible to subscribers and they are perfectly in their right to do TDM themselves and in parallel have this specialised software that makes TDM easier. There is no contradiction.

Tied to this debate but shifting back to a more general angle, a recent report by the EP was mentioned, which found that the Database Directive has completely failed its purpose and should be abolished. At the same time, abolishing it would actually not help much, because those rights would still exist on national level. The same would be true for any element of the Directive we are about to pass now. That's one reason why we have to be very careful that the things we put in the new Directive actually fulfil the purpose we want it to achieve. Changing it or abolishing pieces of it afterwards will be incredibly difficult. The article in the EC-proposal introducing the TDM exception [beside having other issues discussed in part 1 and part 3] lacks clear definition and there is a risk of even more dis-harmonisation among EU member states.

[*The .ZIP file mentioned above comprises a perspective on how copyright should (not) apply to TDM following a welfare economic analysis of copyright (slides by Prof. Poort).]

// All blog posts are the personal opinion of the bloggers. For more information see FutureTDM's DISCLAIMER on how we handle the blog. //