For the legal geeks among us, it is now old news that the European Commission, after promising to modernise copyright, issued a rather unhinged and disappointing copyright review proposal aimed at creating what it claims to be a ‘well-functioning marketplace’. Neighbouring rights aka ancillary copyright for media snippets, robocopyright type content filtering on user uploaded content, mandatory exceptions that can be overridden by Member States or in case of licensing deals (huh?), … you name it: the review has it. There is however one small light at the end of that very skewed and scary-looking tunnel: the copyright review does comprise a mandatory exception for text and data mining (aka TDM) in its Article 3 (with additional explanations in Recitals 8 to 13), a crucial element to enable the use of modern techniques on copyrighted material. To show how important TDM is and what’s at stake, we actually put together a short video which we encourage you to share. (Want to skip directly to our ‘magic recipe’ for a workable TDM exception click here)

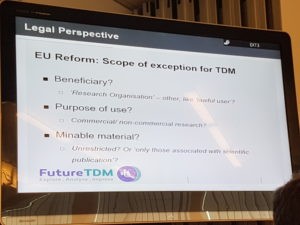

Why is everyone in the research and innovation fields not throwing a party then? Well, because the proposal as drafted by the European Commission comprises considerable flaws, many of which were highlighted at the FutureTDM workshop.

Where the proposed TDM exception gets it right

Test and data mining is defined under Article 2 sub (2) as ‘ any automated analytical technique aiming to analyse text and data in digital form in order to generate information such as patterns, trends and correlations’ and the proposed TDM exception basically reads:

The proposal comprises four positive elements:

- There is an exception: this may seem ridiculous but seeing the lack of ambition of the proposed copyright review, one tends to count one’s blessings these days.

- The exception is mandatory, as opposed to the approach based on voluntary exceptions of the current copyright framework (as set out in the InfoSoc Directive), which results in a patchwork of implementations and total legal uncertainty in an online or cross-border environment.

- The exception explicitly states that contractual bypasses will not be allowed (art 3 par 2). Frankly, such a principle should be applied to all the existing exceptions as one can hardly understand why policy makers spend months crafting exceptions, arguing there every comma, negotiating there scope, scale and detail, to have all of that legislative work brushed aside by one obscure contractual clause that often the parties at the table not holding copyright cannot negotiate. But let us rejoice at least that one exception will get the common sense treatment of ‘the law is worth more than a contract’.

- The exception is not limited to non-commercial activities. This is important as research activities even within institutions such a s universities are often conducted through public-private partnerships or with some form of private funding, which hence makes any restriction to non-commercial unworkable in practice.

Where the proposed TDM exception fails to deliver a positive outcome for Europe

The main legal shortcomings were highlighted in the presentation given by Lucie Guibault, Associate Professor at the Institute for Information Law of the University of Amsterdam, whilst the ‘security & integrity’ addition creates a major practical loophole in the entire legal provision:

- The beneficiaries of the TDM exception are too limited in scope (Article 3 par 1 & Recital 11): the beneficiaries should not be limited to ‘research organisations’ as this is detrimental at two levels: on the one hand, it excludes businesses from benefiting from this exception, at a time where a vibrant start-up community is looking into the potential of these new techniques, and on the other, it excludes individual researchers that are not affiliated to a given research organisations from working in an independent manner if they need to use TDM with legal certainty. The latter also includes investigative journalism, and goes counter to the European Commission’s claim it wants to promote ‘Citizen science‘.

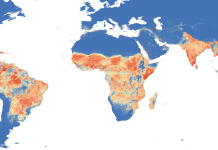

- The purpose of use is too narrowly defined and could give rise to discussions (Article 3 par 3 & Recital 12): the proposed draft only covers ‘scientific research’, an extremely limited scope that could even within the scientific community lead to discussions between the proponents of soft sciences (social sciences) and those that only see the merit of hard sciences (natural sciences). It certainly excludes many innovative uses of TDM that bring benefits to our society (or could have the potential to do so) for no obvious reason.

- The types of material that are covered by the exception could be interpreted in and unduly restrictive manner (Article 3 par 1): can TDM be applied in an unrestricted manner to any type of minable content or does the exception only cover materials ‘associated with scientific publication’?

- The possibility for rightholders to neutralise the exception in practice through so-called security & integrity measures creates a gaping loophole for abuses (Article 3 par 3 & Recital 12): by allowing publishers to introduce random measures to protect the ‘security and integrity’ of their network, the effective use of TDM could simply be rendered impossible, or the use of the publishers own platforms could become the only viable alternative for researchers. There are already known cases of Captcha measures being implemented if researchers want to download articles in bulk (which means algorithms cannot work as human intervention s constantly needed), or measures whereby only one article can be downloaded every 20 seconds (which, as pointed out by Professor Ananiadou from the University of Manchester at the FutureTDM workshop, sounds like a lot but actually means you need 12 years to download 20 million documents). This loophole could allow rightholders to arbitrarily block access for researchers trying to conduct text and data mining. Safeguards in line with those put in place in the context of ‘traffic management’ by telecom operators could be considered (see Article 3 par 3 of the Telecoms Single Market Regulation [EU 2015/2120]), with requirements of proportionality, efficiency, non-discrimination (for example with the security measures applied to researchers’ algorithms vs tose applied to the publishers’ own platform), etc. could be a good starting point to frame this measure.

So what is needed?

The good news is that the Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) present at the FutureTDM Workshop certainly seemed aware that there was room for improvement and willing to tackle the issue. But let’s also be realistic: those were three very well-informed MEPs, out of 751 MEPs in total, so there is a lot of work to be done to inform their colleagues of the need for a proper TDM exception. Whilst the UK opened the door in Europe for a TDM exception, the one they drafted is also far from perfect, if only because they felt that the existing InfoSoc Directive made it impossible for them to adopt a TDM exception that would cover commercial uses, hence making it skewed from the start. Singapore, after introducing fair use a couple of years ago, is now also looking into introducing a TDM exception and, in doing so, is making some valid points in its consultation proposal (see pp. 34-35):

In other words, here are the ingredients for the magic recipe:

- Keep what’s good in the proposed TDM exception: it should be mandatory, not distinguish between commercial and non-commercial and not be bypassed by contractual provisions.

- Expand the scope and scale of the beneficiaries: the beneficiaries should be both natural persons (=human beings) and legal person (=organisations), and should not be limited to research organisations.

- Do not limit the purpose to scientific research, nor the scope of the minable materials.

- Ensure that any security or integrity measures implemented by rightholders are open to a rigorous scrutiny and must abide by a set of parameters that prevent abuse.

(This post was originally published on Copyright for Creativity.)